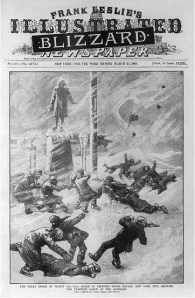

Sandy has humbled New York. As we reflect on what has happened to this great city, Cuban New Yorker cannot do better than simply share with its readers the chronicle that José Martí wrote in 1888 about the great blizzard of that year. “New York Under the Snow” came to my mind when I heard that the last time, before this week, that the New York Stock Exchange had closed for two consecutive days was precisely during the weather event that moved Martí’s pen.

Sandy has humbled New York. As we reflect on what has happened to this great city, Cuban New Yorker cannot do better than simply share with its readers the chronicle that José Martí wrote in 1888 about the great blizzard of that year. “New York Under the Snow” came to my mind when I heard that the last time, before this week, that the New York Stock Exchange had closed for two consecutive days was precisely during the weather event that moved Martí’s pen.

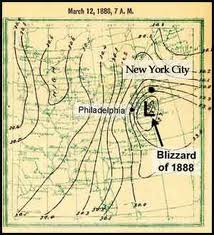

The 1888 blizzard was a snow storm and not a hurricane (although Martí actually uses the word hurricane to describe it), and it occurred late in the winter, practically in the spring. But beyond that, the parallels are uncanny. The 1888 blizzard was also a perfect storm, a collision, precisely over New York, of two cold fronts, one coming from the Northeast and the other from the Midwest. It heralded itself on a Sunday and struck on a Monday. Martí’s chronicle is also eerily familiar: the devastation, the deaths, a proud city humbled and buried by the sheer force of nature, the paralyzed trains and stuck and overturned cars (horse drawn ones, of course), the scarcity of basic commodities after the storm. And there is also the relevance of Martí’s social commentary: the pressure on workers to brave the conditions and show up for work, the questioning of where the railroad companies are sending the relief provisions, the ability of the city to pull together in a time of crisis and overcome its usual selfishness, and the triumph of recovery. But it is clearly another time: there is no mention of a government (much less federal) role in recovery or even an expectation of a role.

It heralded itself on a Sunday and struck on a Monday. Martí’s chronicle is also eerily familiar: the devastation, the deaths, a proud city humbled and buried by the sheer force of nature, the paralyzed trains and stuck and overturned cars (horse drawn ones, of course), the scarcity of basic commodities after the storm. And there is also the relevance of Martí’s social commentary: the pressure on workers to brave the conditions and show up for work, the questioning of where the railroad companies are sending the relief provisions, the ability of the city to pull together in a time of crisis and overcome its usual selfishness, and the triumph of recovery. But it is clearly another time: there is no mention of a government (much less federal) role in recovery or even an expectation of a role.

Below is virtually the entire chronicle. I took out some small passages that were redundant or just too baroque, Martí style. I used primarily the translation that  appears in pages 271-277 of Phillip Lopate’s Writing New York: A Literary Anthology. New York: Washington Square Press, 1998, available as a preview through Google Books. Lopate does not credit the translator, so I cannot. Working from the Spanish original in the Obras Completas, I tinkered a bit with the translation. Also, the version in Google had missing passages, which I had to translate myself. I did the best I could: it is not easy to translate Martí. His sentence structures and punctuation work well in Spanish, but not in English. But the man wrote with a sensibility that speaks to us today, especially during these dark New York days. I hope that the redemptive and hopeful tone of his ending lifts your spirits.

appears in pages 271-277 of Phillip Lopate’s Writing New York: A Literary Anthology. New York: Washington Square Press, 1998, available as a preview through Google Books. Lopate does not credit the translator, so I cannot. Working from the Spanish original in the Obras Completas, I tinkered a bit with the translation. Also, the version in Google had missing passages, which I had to translate myself. I did the best I could: it is not easy to translate Martí. His sentence structures and punctuation work well in Spanish, but not in English. But the man wrote with a sensibility that speaks to us today, especially during these dark New York days. I hope that the redemptive and hopeful tone of his ending lifts your spirits.

NEW YORK UNDER THE SNOW

José Martí

March 15, 1888

Published in La Nación (Buenos Aires), April 27, 1888

The first oriole had already been spied hanging its nest from a cedar in Central Park; the bare poplars were putting forth their spring fuzz; and the leaves of the chestnut were emerging, like chattering women poking their heads out of their hoods after a storm. Notified by the chirping of the birds, the brooks were coming out from under their icy covering to see the sun’s return, and winter, defeated by the flowers, had fled away, covering its retreat with the month of winds. The first straw hats had made their appearance, and the streets of New York were gay with Easter attire, when, on opening its eyes after the hurricane has spent its force, the city found itself silent, deserted, shrouded, buried under the snow. Doughty Italians, braving the icy winds, load their street-cleaning carts with fine, glittering snow, which they empty into the river to the accompaniment of neighs, songs, jokes, and oaths.

The first oriole had already been spied hanging its nest from a cedar in Central Park; the bare poplars were putting forth their spring fuzz; and the leaves of the chestnut were emerging, like chattering women poking their heads out of their hoods after a storm. Notified by the chirping of the birds, the brooks were coming out from under their icy covering to see the sun’s return, and winter, defeated by the flowers, had fled away, covering its retreat with the month of winds. The first straw hats had made their appearance, and the streets of New York were gay with Easter attire, when, on opening its eyes after the hurricane has spent its force, the city found itself silent, deserted, shrouded, buried under the snow. Doughty Italians, braving the icy winds, load their street-cleaning carts with fine, glittering snow, which they empty into the river to the accompaniment of neighs, songs, jokes, and oaths.  The elevated train, stranded in a two-day vigil beside the body of the engineer who set out to defy the blizzard, is running again, creaking and shivering, over the clogged rails that glitter and flash. Sleigh bells jingle; the newsvendors cry their papers; snow-plows, drawn by stout percherons, throw up banks of snow on both sides of the street as they clear the horse car’s path; through the breast-high snow, the city makes its way back to the trains, paralyzed on the white plains, to the rivers, now turned into bridges, to the silent wharfs.

The elevated train, stranded in a two-day vigil beside the body of the engineer who set out to defy the blizzard, is running again, creaking and shivering, over the clogged rails that glitter and flash. Sleigh bells jingle; the newsvendors cry their papers; snow-plows, drawn by stout percherons, throw up banks of snow on both sides of the street as they clear the horse car’s path; through the breast-high snow, the city makes its way back to the trains, paralyzed on the white plains, to the rivers, now turned into bridges, to the silent wharfs.

The clash of the combatants echoes through the vault-like streets of the city. For two days the snow has had New York in its power, encircled, terrified, like a prize fighter to the canvas by a sneak punch. But the moment the attack of the enemy slackened, as soon as the blizzard had spent its first fury, New York, like the  victim of an outrage, goes about freeing itself from its shroud. Leagues of men move through the white mounds. The snow already runs in dirty rivers in the busiest streets under the onslaught of its assailants. With spades, with shovels, with their own chests and those of the horses, they push back the snow, which retreats to the rivers.

victim of an outrage, goes about freeing itself from its shroud. Leagues of men move through the white mounds. The snow already runs in dirty rivers in the busiest streets under the onslaught of its assailants. With spades, with shovels, with their own chests and those of the horses, they push back the snow, which retreats to the rivers.

Man’s defeat was great, but so was his triumph. The city is still white; the bay remains white and frozen. There have been deaths, cruelties, kindness, fatigue, and bravery. Man has given a good account of himself in this disaster.

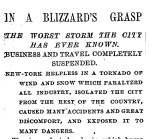

At no time in this century has New York experienced a storm like that of March 13. It had rained the preceding Sunday, and the writer working into the dawn, the newspaper vendor at the railroad station, the milkman on his round of the sleeping houses, could hear the whiplash of the wind that had descended on the  city against the chimneys, against walls and roofs, as it vented its fury on slate and mortar, shattered windows, demolished porches, clutched and uprooted trees, and howled, as though ambushed, as it fled down the narrow streets. Electric wires, snapping under its impact, sputtered and died. Telegraph lines, which had withstood so many storms, were wrenched from their posts. And when the sun should have appeared, it could not be seen, for like a shrieking, panic-stricken army, with its broken squadrons, gun carriages and infantry, the snow swirled past the darkened windows, without interruption, day and night. Man refused to be vanquished. He came out to defy the storm.

city against the chimneys, against walls and roofs, as it vented its fury on slate and mortar, shattered windows, demolished porches, clutched and uprooted trees, and howled, as though ambushed, as it fled down the narrow streets. Electric wires, snapping under its impact, sputtered and died. Telegraph lines, which had withstood so many storms, were wrenched from their posts. And when the sun should have appeared, it could not be seen, for like a shrieking, panic-stricken army, with its broken squadrons, gun carriages and infantry, the snow swirled past the darkened windows, without interruption, day and night. Man refused to be vanquished. He came out to defy the storm.

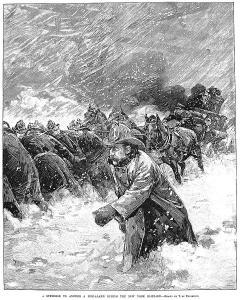

But by this time the overpowered streetcar lay horseless beneath the storm; the elevated train, which paid in blood for its first attempt to brave the elements, let the steam escape from its helpless engine; the suburban train, halted en route by  the tempest or stalled by the drifting snow, higher than the engines, struggled in vain to reach its destination. The streetcars attempted one trip, and the horses plunged and reared, defending themselves with their hoofs from the suffocating storm. The elevated train took on a load of passengers, and ground to a halt half-way through the trip, paralyzed by the snow; after six hours of waiting, the men and women climbed down by ladder from their wind-tossed prison. The wealthy, or those faced with an emergency, paid twenty-five or fifty dollars for carriages drawn by stout horses to carry them a short distance, step by step. The angry wind, heavy with snow, buffeted them, pounded them, hurled them to the ground.

the tempest or stalled by the drifting snow, higher than the engines, struggled in vain to reach its destination. The streetcars attempted one trip, and the horses plunged and reared, defending themselves with their hoofs from the suffocating storm. The elevated train took on a load of passengers, and ground to a halt half-way through the trip, paralyzed by the snow; after six hours of waiting, the men and women climbed down by ladder from their wind-tossed prison. The wealthy, or those faced with an emergency, paid twenty-five or fifty dollars for carriages drawn by stout horses to carry them a short distance, step by step. The angry wind, heavy with snow, buffeted them, pounded them, hurled them to the ground.

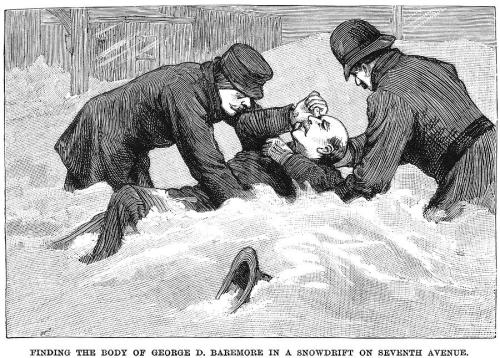

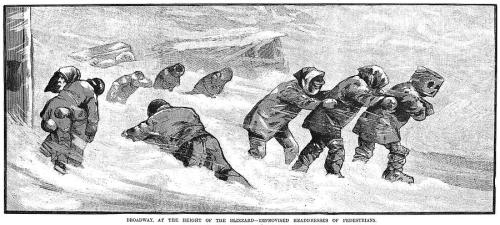

It was impossible to see the sidewalks. Intersections could no longer be distinguished, and one street looked like the next. On Twenty-third Street, one of the busiest thoroughfares, a thoughtful merchant put a sign on a corner-post: “This is 23rd Street.” The snow was knee-deep, and the drifts, waist-high. The angry wind nipped at the hands of pedestrians, knifed through their clothing, froze their noses and ears, blinded them, hurled them backward into the slippery snow, its fury making it impossible for them to get to their feet, flung them hatless and groping for support against the walls, or left them to sleep, to sleep forever, under the snow. A shopkeeper, a man in the prime of life, was found buried today, with only a hand sticking from the snow to show where he lay. A messenger boy, as blue as his uniform, was dug out of a white, cool tomb, a fit resting place for his innocent soul, and lifted up in the compassionate arms of his comrades. Another, buried to the neck, sleeps with two red patches on his white cheeks, his eyes a filmy blue.

froze their noses and ears, blinded them, hurled them backward into the slippery snow, its fury making it impossible for them to get to their feet, flung them hatless and groping for support against the walls, or left them to sleep, to sleep forever, under the snow. A shopkeeper, a man in the prime of life, was found buried today, with only a hand sticking from the snow to show where he lay. A messenger boy, as blue as his uniform, was dug out of a white, cool tomb, a fit resting place for his innocent soul, and lifted up in the compassionate arms of his comrades. Another, buried to the neck, sleeps with two red patches on his white cheeks, his eyes a filmy blue.

The old, the young, women, children, inch along Broadway and the avenues on their way to work. Some fall, and struggle to their feet. Some, exhausted, sink into a doorway, their only desire to struggle no more; others, generous souls, take them by the arm, encouraging them, shouting and singing. An old woman, who had made herself a kind of mask of her handkerchief with two slits for the eyes, leans against a wall and bursts into tears; the president of a neighboring bank, making his way on foot, carries her in his arms to a nearby pharmacy, which can be made out through the driving snow by its yellow and green lights. “I’m not going any further,” said one. “I don’t care if I lose my job.” “I’m going on,” says another. “I need my day’s pay.” The clerk takes the working girl by the arm; she helps her weary friend with an arm around his waist. At the entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge, a new bank clerk pleads with the policeman to let him pass, although at that moment only death can cross the bridge. “I will lose the job it has taken me three years to find,” he supplicates. He starts across, and the wind reaches a terrible height, throws him to the ground with one gust, lifts him up again, snatches off his hat, rips open his coat, knocks him down at every step; he falls back, clutches at the railing, drags himself along. Notified by telegraph from Brooklyn, the police on the New York side of the bridge pick him up, utterly spent.

But why all this effort, when hardly a store is open, when the whole city has surrendered, huddled like a mole in its burrow, when if they reach the factory or office they will find the iron doors locked? Only a fellow man’s pity, or the power of money, or the happy accident of living beside the only train which is running in one section of the city, valiantly inching along from hour to hour, can give comfort to so many faithful employees, so many courageous old men, so many heroic factory girls on this terrible day. From corner to corner they make their way, sheltering themselves in doorways, until one opens to the feeble knocking of their numbed hands, like sparrows tapping against the window panes. Suddenly the fury of the wind mounts; it hurls the group fleeing for shelter against the wall; the poor working women cling to one another in the middle of the street until the snarling, screeching wind puts them to flight again. Men and women fight their way uptown, struggling against the gale, clearing the now from their eyes, shielding them with their hands to find their way through the storm. Hotels? The chairs have been rented out for beds, and the baths for rooms. Drinks? Not even the men can find anything to drink; the saloons have exhausted their stock; and the women, dragging their numb feet homeward, have only tears to drink.

women fight their way uptown, struggling against the gale, clearing the now from their eyes, shielding them with their hands to find their way through the storm. Hotels? The chairs have been rented out for beds, and the baths for rooms. Drinks? Not even the men can find anything to drink; the saloons have exhausted their stock; and the women, dragging their numb feet homeward, have only tears to drink.

After the first surprise of the dawn, people find ways to adjust their clothing so the fury of the tempest will not do them so much harm. There is an overturned wagon at every step; a window shade, hanging from its spring, flaps against the wall like the wing of a dying bird; an awning in shreds, a half-torn cornice, a fallen eave . . . “Sir!” cries the voice of a boy who cannot be seen for the snow, “get me out of here, I will die.” It is a messenger boy that some vile firm has sent out to deliver a message. And when the night closed in without lights, when there was space only for fear . . . when from houses without roofs people searched in vain for their families, when the fire hydrants lie buried beneath five feet of snow, a fire erupts furiously, a fire that brings down three houses. The fire truck arrives! And the firemen dig with their hands to find the hydrants . . .

Without milk, without coal, without newspapers, without streetcars, without telephones, without telegraph, the city awoke this morning. And last night there were four open theaters! All businesses suspended, and the false marvel of the elevated train pushes in vain to take to work the mob that crowds the station waiting impatiently.

The trains have stalled with their human cargo. Nothing has been heard from the rest of the nation. The rivers are ice and the daring ones are crossing them on foot. Suddenly the ice cracks and floes are formed with men clinging to them: a tugboat goes out to save them, pushing the floating ice towards the piers. They are saved, and from the river banks one hears one loud “Hurray!” “Hurray” they yell on the streets at the passing fireman, the policeman, the brave mailman. What has happened to the trains that do not arrive, and where do the railroad companies, with their magnificent energy resources, with their most powerful engines, send the groceries and the coal? How many bodies under the snow?

The snow, as if it were an army in retreat that turns back on the enemy with an unexpected attack, came at night and covered with death the proud city.

We saw yesterday that these attacks from the unknown are worthwhile for utilitarian peoples whose virtues, nurtured by their labor, are capable of compensating, in these solemn hours, for the lack of those virtues that are weakened by selfishness. How brave the children, how punctual the workers, how unhappy and noble the women, how generous the men! The entire city speaks in a loud voice, as if afraid to be lonely. Those who all year long brutally elbow each other, today laugh, they exchange their stories of mortality, exchange addresses, and accompany their new friends for long walks . . .

It terrifies and amazes to see this city of snow reappear, with its red houses, as if flowering in blood. The telegraph poles ruefully contemplate the destruction, their tangled, fallen wires like unkempt heads. The city resuscitates, buries its dead, and with men, horses, and machines all working together, clears away the snow with streams of boiling water, with shovels, plows, and bonfires. But one is touched by a sense of great humility and a sudden rush of kindness, as though the dread hand had touched the shoulders of all men.