P.S. 62 is in the South Bronx. It has about 700 students, 79 percent Hispanic and 18 percent Black. Test scores are below state and city averages. Only 19 percent of 5th graders in 2016-17 met state standards on the New York State English test and 27 percent met the standards in math. But there are encouraging signs: the teacher-student ratio is down, parents laud the dedication of the teachers and the leadership of the school, and considerable progress has been noted in recent years in raising the academic achievement of the students. Everything points to a school where everyone is trying hard to make a difference in the lives of students. [See the data on P.S. 62 here].

It may not help much, but perhaps P.S. 62 could also try to change its name to one more likely to inspire its faculty and students.

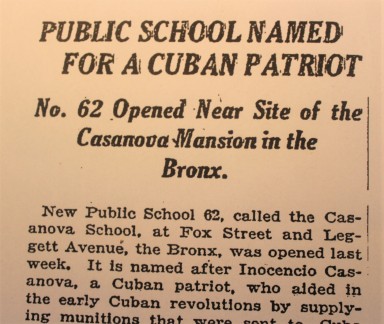

P.S. 62 was named in honor of one “Inocensio Casanova.” It was given the name on the very day the school was inaugurated: June 11, 1922. According to the New York Times article on the opening of the school, Casanova was “a Cuban patriot, who aided in the early Cuba revolution by supplying munitions that were sent to Cuba from the Casanova mansion, which formerly stood near the present school site.”

As far as I know, Casanova’s foremost claim to fame is that he has a New York City Public School named after him. No small feat, since he is, as far as I can tell, the only Cuban who has such an honor. Towering figures of Cuban history, such as José Martí or Félix Varela lived most of their adult lives in New York and did important things here, and Cubans such as Luciano (Chano) Pozo or Mongo Santamaría or Arsenio Rodríguez brought their music to the city and gave jazz its Latin tinge. Those prominent Cubans do not have New York City schools named after them. But somehow “Inocensio” does. It would be interesting to research who, back in 1922, championed placing his name on the school. As for labeling him as a patriot for smuggling armaments from his house, we’ll leave that for later.

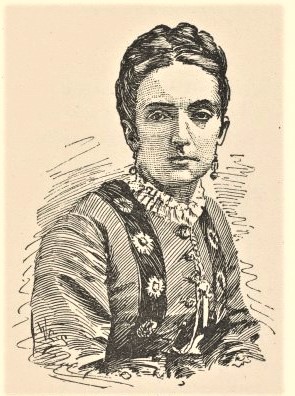

But I am being unfair. “Inocensio” has at least one other important accomplishment he can claim besides the school: he fathered Emilia Casanova, a well-known figure in Cuban history largely because of what she did in New York. There are biographies of Emilia. She figures prominently in the pantheon of patriotic Cuban women. On the other hand, there are no biographies of her father and it is not likely that I or any another student of Cuban history would have ever heard of him if not for Emilia. I have not been able to find a picture or drawing of him, and a Google search of his name yields only P.S. 62.

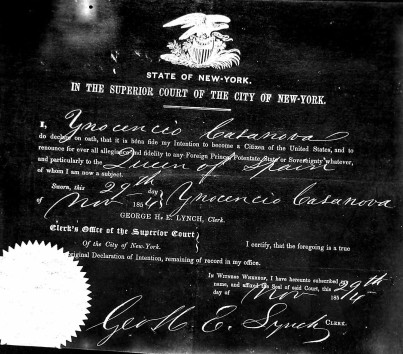

Let’s start the story from the beginning, in Cuba, of course. But first, a spelling issue. The namesake of the school was not named Inocensio, but Inocencio. In fact, he spelled it Ynocencio, as is clear from his own handwriting on both his U.S. citizenship application (1854) and his 1867 application for a U.S. passport (traditionally the Y and I were used interchangeably). It is not clear how it became Inocensio in the New York City Public Schools records because the New York Times had it right (Inocencio) when it reported on the opening of the school in 1922.

Ynocencio’s 1854 U.S. citizenship application

Ynocencio’s 1867 U.S. passport application

The Cuban-born Ynocencio (I’ll use his spelling) Casanova and his wife Petronia Rodríguez, a native of the Canary Islands, lived in Cárdenas, a city in the Cuban region of Matanzas, east of Havana. They had sixteen children, including Emilia, who was born in 1832 and who very early gave evidence of what one of her biographers called a “willful character.” Her personality was matched by her appearance. By age twelve she had, according to one biographer, “the physical development of a young woman of fifteen, and her athleticism gave her a vigorous presence that matched her headstrong behavior.” The Casanova household was frequently thrown into disarray because of her

- Emilia Casanova

obstinacies in pursuing her projects and whims. At age eighteen, the independence of Cuba became her purpose in life, the channel for her passion and energy, and a huge headache for Ynocencio, who despite not being an active supporter of Cuban separatism, found that his family came under increasing scrutiny from the colonial authorities for his daughter’s public criticisms of Spanish rule.

In the summer of 1852 Ynocencio Casanova decided it was best to temporarily relocate his family to the United States, where, after visiting New York, Niagara Falls, Saratoga, and Albany, they settled in Philadelphia. It was there in 1854 that Emilia, at age twenty-two, married Cirilo Villaverde, twenty years her senior, who impressed her with a résumé of sacrifice on behalf of Cuban separatism (Cirilo is another Cuban New Yorker who is a worthy candidate as a school namesake; more on him later). Emilia and Cirilo stayed in the United States and moved to New York when her family returned to Cuba. Eventually they had three children, although their only daughter died before her seventh birthday.

Throughout the rest of their lives, the couple remained active in New York émigré politics. They were involved in 1866 in the creation of the Junta Republicana de Cuba y Puerto Rico. In 1867 Emilia, anticipating the coming war for Cuba’s independence, prevailed upon her father to liquidate his assets in Cuba and move permanently to New York. For $150,000 dollars Ynocencio bought the old Leggett mansion on Oak Point, in what is now the Hunts Point area in the Bronx, very near where P.S. 62 is located. Originally part of the estate of the family of writer and political reformist William Leggett, the house had been totally renovated by a wealthy New York grocer named Benjamin Whitlock, who built vaults underneath the house to store wine. Whitlock lost most of his fortune with the decline in the cotton trade during the Civil War, and the house was shuttered when the Casanovas bought it in November of 1867.

When the war for Cuban independence broke out the following year, Emilia fervently threw herself into the task of organizing expeditions to take men and arms to the rebels to Cuba. Emilia turned the house on Hunts Point into a hotbed of militant activity in the New York area. It was Ynocencio’s house, but, as had always been the case, he was primarily a bystander to Emilia’s intense activism. The mansion’s vaults were converted into storehouses for guns, rifles, powder, and ammunition. Its relatively isolated location near the coast made it ideal for discreetly smuggling ordnance out to the East River or to the Long Island Sound for shipment to Cuba. The neighbors were aware of the secret activities going on, and years later, after the Casanovas moved out and it stood deserted, the house retained a mysterious reputation. As Stephen Jenkins, a historian of the Bronx, wrote in 1912:,

. . . the visits of the dark-skinned, mysterious-looking men ceased, and the house was deserted; while whispers of murdered Spanish spies and of ghosts and strange and unaccountable noises in the vacant house filled the neighborhood. . . so many weird tales were told about the old mansion that its demolition was watched with intense interest.

In addition to helping outfit expeditions from the Bronx, Emilia Casanova traveled to Manhattan almost daily organizing fundraising events. In January of 1869 she established the organization La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba (The League of Cuba’s Daughters) as a way of organizing the Cuban ladies of the city on behalf of the insurgents. It also served as her political platform. The League was the first ever political association organized by a Cuban woman. In March, the League sponsored a theatrical performance that raised nearly $4,000 for the Cuban cause. Emilia was also a prolific letter writer, staying in touch with Cubans, especially ladies, living in different parts of the world, corresponding even with Cuban generals on the battlefield, and soliciting support for the cause of independence from members of the U.S. Congress and from world leaders. She reportedly met with President Grant and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish on more than one occasion. Her correspondence reveals that she wielded an acerbic pen, lashing out at Cubans in New York who she felt were doing less than their fair share for the cause of an independent Cuba.

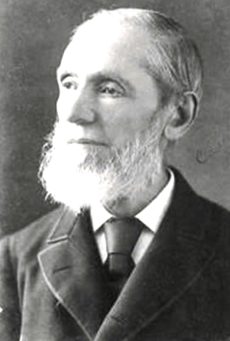

The war ended in 1878 without achieving Cuban independence. Emilia and Cirilo remained in New York, where in 1880 the U.S. Census found them living in Harlem, at 46 East 126th Street, across the street from Ynocencio and the rest of the Casanova family, who lived at number 49. It was there, in Harlem, that Emilia’s husband, Cirilo Villaverde,

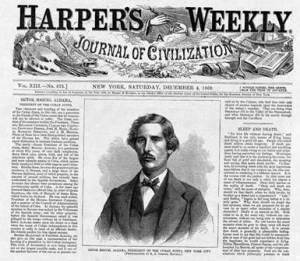

Cirilo Villaverde

completed, with Emilia’s help, the classic Cuban novel, Cecilia Valdés, ó la loma del ángel. It was published in New York in 1883. Most critics regard it as the most important Cuban novel of the nineteenth century.

Cirilo Villaverde died in New York in 1894, a year before the start of the final and definitive Cuban war of independence. His death did not in any way minimize the impassioned activism that his wife had demonstrated during the nearly half a century of the couple’s residence in New York. Upon Cirilo’s death, Emilia traveled briefly to Havana to bury her husband in the capital’s Colón necropolis, but returned to New York, where she remained ready to support not just with words, but also with firepower, the new war against Spanish control of the island. Her correspondence reveals that in 1894 she was stockpiling Winchester carbines and ammunition in her home in midtown Manhattan to send to Cuba, much as she had done twenty-five years earlier at Hunt’s Point. Emilia Casanova died in New York in 1897 before witnessing a Cuba free of Spanish control. She was twenty years younger than Cirilo, but survived him by only three years. She was interred in St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. It was not until 1944 that her son Narciso fulfilled her wish to be buried next to her husband in Havana.

My humble proposal is that P.S. 62 in the Bronx continues to be named after a Casanova, but not Ynocencio. Emilia was the true Cuban patriot who shipped arms and ammunition from the former Leggett Mansion near where the school is now located. Ynocencio was just along for the ride. There is no evidence that he was active in émigré separatist activities. Maybe the New York City school administrators knew this in 1922 when the school was dedicated and simply chose not to name the school after a woman. Or maybe they did not know about Emilia’s activities. But we now know of her courage and her impassioned commitment to a cause to which she dedicated her life, a woman who could not be discouraged from pursuing her goals. That is not a bad example for the deserving faculty and students at P.S. 62.

- One of the first kindergarten classes at P.S. 62

[I want to acknowledge that my son, Lisandro Pérez-Rey, first called to my attention the name of P.S. 62]

the deterioration over the past two years in the reliability of subway service. Once the outcry went up, the Governor went down from Albany and showed his face, appointed a new director of the MTA, investments were made in the infrastructure, and scheduled maintenance work stepped up noticeably. I have every expectation than when I return to New York service will have noticeably improved. New Yorkers demand good service. They may not always get it, but there is an expected level of performance that pushes the institutions that serve the public to do better, to remedy the situation, to set a higher bar. Maybe that’s because New Yorkers pay for it, in the form of both state and city income taxes, as well as in higher prices for just about everything else. It’s a New York mantra: you pay more, but you expect more. That applies to everything from municipal services, restaurants, cultural events, and even to seats at Yankee Stadium. Admittedly, the downside of that is that the city is pricing out all but its more affluent residents, as the gentrification of working class and ethnic neighborhoods continues apace.

the deterioration over the past two years in the reliability of subway service. Once the outcry went up, the Governor went down from Albany and showed his face, appointed a new director of the MTA, investments were made in the infrastructure, and scheduled maintenance work stepped up noticeably. I have every expectation than when I return to New York service will have noticeably improved. New Yorkers demand good service. They may not always get it, but there is an expected level of performance that pushes the institutions that serve the public to do better, to remedy the situation, to set a higher bar. Maybe that’s because New Yorkers pay for it, in the form of both state and city income taxes, as well as in higher prices for just about everything else. It’s a New York mantra: you pay more, but you expect more. That applies to everything from municipal services, restaurants, cultural events, and even to seats at Yankee Stadium. Admittedly, the downside of that is that the city is pricing out all but its more affluent residents, as the gentrification of working class and ethnic neighborhoods continues apace. When I arrived in Miami I saw piles of debris lining the streets from a hurricane that came through nearly a month before, with no sign that anyone was coming around to pick them up. And as far as I could tell, there was a deafening silence in the media (from mainstream to social) about it, as if that is the expected level of performance from those responsible for providing public services. I also hear horror stories from relatives about waiting more than an hour or two in a doctor’s office. At a department store where I went to return an item, I took a number at the customer service desk only to find that there was just one taciturn clerk on duty and sixteen people ahead of me, all of them with a look of resignation on their faces. New Yorkers don’t put up with that and those providing services, from doctors to retail outlets, know it. The transformation of the Marlins into a AAA team by a management interested in only the bottom line is the most evident example of the lack of respect for consumers that seems to pervade down here.

When I arrived in Miami I saw piles of debris lining the streets from a hurricane that came through nearly a month before, with no sign that anyone was coming around to pick them up. And as far as I could tell, there was a deafening silence in the media (from mainstream to social) about it, as if that is the expected level of performance from those responsible for providing public services. I also hear horror stories from relatives about waiting more than an hour or two in a doctor’s office. At a department store where I went to return an item, I took a number at the customer service desk only to find that there was just one taciturn clerk on duty and sixteen people ahead of me, all of them with a look of resignation on their faces. New Yorkers don’t put up with that and those providing services, from doctors to retail outlets, know it. The transformation of the Marlins into a AAA team by a management interested in only the bottom line is the most evident example of the lack of respect for consumers that seems to pervade down here.

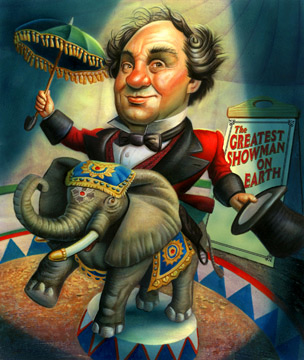

The lens of history renders it an extraordinary sight: the builder of the Cuban nation and its most revered military figure, icons both, sitting together enjoying the “Greatest Show on Earth.” That spring of 1894 Barnum & Bailey’s featured attraction was a pair of large chimpanzees, “Chiko and his bride Johanna,” whose trained act was a parody of the bliss and agony of human matrimonial life. Judging from the advertisement in the New York Times, the three-ring circus at Madison Square that season was an extravaganza:

The lens of history renders it an extraordinary sight: the builder of the Cuban nation and its most revered military figure, icons both, sitting together enjoying the “Greatest Show on Earth.” That spring of 1894 Barnum & Bailey’s featured attraction was a pair of large chimpanzees, “Chiko and his bride Johanna,” whose trained act was a parody of the bliss and agony of human matrimonial life. Judging from the advertisement in the New York Times, the three-ring circus at Madison Square that season was an extravaganza:

Exhibit visitors gazing with interest at a plastic model of a fritura de malanga, marveling at the combination of a slice of guayaba paste with cream cheese on a cracker. A plate of moros. Imagine. What an exotic world.

Exhibit visitors gazing with interest at a plastic model of a fritura de malanga, marveling at the combination of a slice of guayaba paste with cream cheese on a cracker. A plate of moros. Imagine. What an exotic world.