Cristóbal Mádan y Mádan meets the criteria I set out in my June 21st blog post for identifying the first true Cuban New Yorker. He was already in the city when Félix Varela arrived. He was involved in movements to sever Cuba from Spain, so he thought of himself as a Cuban, and he certainly had an enduring (if not always continuous) presence in New York City that possibly spanned as many as seven decades. In fact, Mádan is a Zelig-type of figure in the history of Cuban New York. Or perhaps he is closer to Forrest Gump.

I don’t mean by that comparison that he was a comic figure (and I certainly do not mean any disrespect). What I mean by the comparison is that, like Forrest Gump, or Zelig, Mádan was a fairly nondescript low-profile sort of guy who was not among the most prominent historical figures, yet managed to be connected with all the major players of his day, his name surfacing almost unexpectedly at various critical points from 1823 all the way to the 1870s. In other words, he was a recurring background figure in the story of Cuban New York.

I suspect that in large measure he had a low profile because he preferred it that way. He published his political essays under a pseudonym, for example. As with most behind-the-scenes personages he was not doubt a much more important player than what the historical record reveals. But the fact is that I cannot post here a drawing, painting, or a photograph of him because I have not been able to find one, nor do I know exactly when or how or where he died or where he is buried. [If anyone can fill those gaps I would appreciate hearing from you].

The Mádans originated in Waterford, Ireland, where the name was probably spelled Madden. Cristobal’s grandfather migrated to Havana by way of the Canary Islands around the time of the British occupation of the city, the right moment to get in on the ground floor of the sugar boom. The family lived in Havana, but their mills were in the Matanzas region.

Cristóbal was named after his maternal grandfather, who was also his father’s uncle. Cristóbal’s father, Joaquín, had married a first cousin, Josefa Nicasia Mádan (not unusual among landed elites everywhere, like, say, Ashley Wilkes and Melanie Hamilton). Joaquín and Josefa had six children, of which Cristóbal was the youngest and the only male. After his wife died, Joaquín married yet another first cousin, Josefa’s sister. They had no children.

As with most of the newly-rich sugarocacy, the Madans sold their sugar in New York, where the “counting houses” that lined South Street acted as the selling agents, keeping accounts for them and investing their money. When he was about to turn sixteen, in the summer of 1822, Cristobal was sent to New York to learn English, study, and gain experience in the city’s mercantile world. Arrangements were made for him to intern as a clerk in the counting house of Jonathan Goodhue at 44 South Street, just south of Maiden Lane. Goodhue was

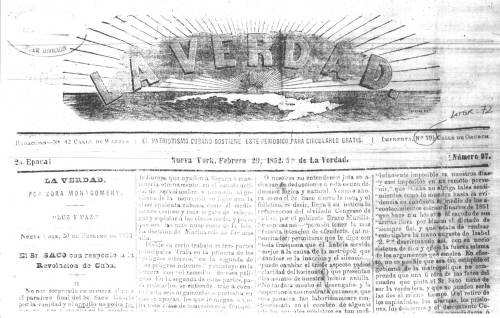

“View of South Street, From Maiden Lane,” by William James Bennett, 1827

“View of South Street, From Maiden Lane,” by William James Bennett, 1827

a New Englander who was engaged in importing sugar from the mills of the Madans and other Cuban producers. It was there that “Cristobalito” greeted his former teacher, Father Félix Varela, when the priest arrived in Manhattan on December 15, 1823. One week later, Mádan also welcomed to the city a friend from Matanzas: the poet José María Heredia. Cristóbal helped both of those prominent Cubans find housing and establish a foothold in the city.

Heredia would address him facetiously as “My Dear Consul,” referring in a letter to Mádan to the “laborious and sterile job the Republic has entrusted to you” in New York (a “Republic” that at that time existed only in the thoughts of Varela and Heredia).

But an independent Cuban Republic was probably not in the mind of Cristóbal Mádan. By the time he was in his forties he emerged again in the history of Cuban New York as a committed advocate of Cuba’s annexation to the United States. The 1850 U.S. Census found him living in the fashionable Madison Square Park area with his second wife Mary, six children, and eight servants. That same year he also became a U.S. citizen. That is not to say that he

lived continuously in New York. Mádan led what we would call today a transnational life, dividing his time between New York, Havana, and Matanzas. All of his children, for example, were born in Cuba.

Cristóbal Mádan played an important behind-the-scenes role in the movement that so many of his fellow sugar producers favored: annexationism. The sugarocracy believed it was in their best interest for Cuba to join the Union as a slave state. Cristóbal wrote anonymously for the annexationist newspaper in New York, La Verdad, which he probably also helped to bankroll. And he was

also responsible for connecting his fellow sugarocrats with influential Americans who favored annexing Cuba. It is not difficult to see why he was the point man for that connection. His second wife Mary was a New York Irish-American named Mary O’Sullivan, the sister of John L. O’Sullivan, an influential New York Democrat and a committed expansionist who is credited with coining the term “Manifest Destiny.” O’Sullivan convinced President James Polk to make an offer to Spain to buy Cuba, an offer that was, of course, roundly rejected by Madrid.

Cristóbal emerges again in New York among the refugees from the war for independence that started in 1868. Already in his sixties, his economic situation was in a tailspin with the embargo of properties that the Spanish leveled against Cubans who left the island. The war had created a large community of displaced Cubans in New York, and Cristóbal returned to his role as the city’s “unofficial Cuban Consul,” using his longstanding contacts with city officials and with the Catholic archdiocese to help Cubans in need.

Mádan probably returned to Cuba after the end of the war in 1878 to try to recover his embargoed properties, something many other Cuban New Yorkers also tried to do, with no success. The treaty that ended the war guaranteed amnesty and a safe return to exiled Cubans, but was silent on returning embargoed properties.

Cristóbal probably lived out his life in Havana attending to his law practice, which also tied him to the next stage in the development of Cuban New York. His law office once hired a young teenaged intern by the name of José Martí.

So the case for Mádan as the first Cuban New Yorker is a strong one. He arrived before – in fact greeted – two of the towering figures of Cuban New York: Varela and Heredia. He had a deep and abiding, if not always permanent, connection with the city his entire life. His political activities make clear that he identified not as Spanish, but as Cuban. Of course, he did not have the impact that Varela had on New York. And we would need to be reconciled to the idea that the first Cuban New Yorker was an annexationist and a slave owner.

In a future blog, the case for Varela.

How interesting! I love that he describes his occupation as “gentleman”. Those were the days!

Cristóbal was consistently a gentleman — his 1850 Census form lists that as his “occupation”.

Great blog! I wrote my dissertation about a Cuban who moved to NY in the late 1870s, became a Baptist, and moved back and forth between Havana, New York, and (if you can believe it) the US South, mostly Atlanta, for the next ~40 years. He was very politically active (an independentista) and had a fascinating relationship with the Southern Baptist Convention which lasted until about 1901, when his independentista views began to annoy the SBC. I’ve always wanted to know more about his time in NY. Looking forward to more historical posts!

I would be very interested in consulting your dissertation. Please send me the reference. Also, I could look up your historical Cuban if you send me his name to see if he shows up in any of the records I have of Cuban New Yorkers.

There is a street in the Bronx by Brush Ave. named Yznaga Pl. It was named either for Jose Aniceto Iznaga Borrell, the Cuban Patriot, for his efforts from 1819 to 1860 in the Cuban independence or for his nephew Antonio Iznaga del Valle, sugar trader and cotton plantation owner in La. and Cuba. Antonio’s son Fernando became a very prominent banker with the firm of H. B. Hollins & Co. Antonio;s daughters married British Royalty, Consuelo was the Duchess of Manchester and his other daughter Natica was Lady Lister – Kaye. There is an Yznaga Ave, in Newport, RI also.

do you happen to know if Luis Pedroso y Madan who married Maria Sturdza (daughter of Dimitrie Sturdza) is the grandson Of Cristobal Madan and Mary O’Sullivan. Their daughter Maria Delores Madan married Jose Pedroso and I think they had a son named Luis. I wonder if he is one and the same.

I have no idea, I am involved in Iznaga genealogy mainly

It is likely that Luis is a grandson of Cristóbal Mádan, since, as you indicate, his name was Luis Pedroso y Mádan. That would indicate that he is probably the son of María de los Dolores Mádan y O’Sullivan, daughter of Cristóbal, who married José Francisco Pedroso y Cárdenas in the Church of St. Francis Xavier in New York on May 12, 1869. My information, of course, comes from volume 5, p. 167 of the Historia de Familias Cubanas by Francisco Xavier de Santa Cruz y Mallen (La Habana, Editorial Lex, 1944). Beyond the information on the marriage, Santa Cruz provides no information on the children (if any) of the couple — which is unusual.

yes luis pedroso is the grandson of Cristobal Madan and Mary o’ Sullivan.

my brothers(french/ my mother was Pedroso ) and my Pedroso Cousins ( spain)are descendants pf luis pedroso ‘ younguest brother Fernando Pedroso y madan;

My cousins in spain have a portrait of our great great grandfather Madan,

Hello Christine,

I am sorry that only now I have seen your comment.

Do you happen to know where Cristóbal Madan died and where he is buried?

Lisandro

Cristóbal Fermín Buenaventura del Carmen Madan (y Madan) died in Havana on 13 April 1889 of “nefritis parenquimatosa.” His funeral took place on the 14th at Montserrate Catholic Church in Havana and he was buried that day in Colón Cemetery. I would LOVE to get a copy of an image of him.

Very interesting article! Where did you find all of the information on his life? My father is looking for our Madan family tree to find the connection. I know his name appears on it. This website talks about the first Madan to go to Cuba from Ireland, from which we decend: http://www.irlandeses.org/0711fernandezmoya2.htm

It is not so hard to find the Madan family tree. It can be found in Historia de familias cubanas, por Francisco Xavier de Santa Cruz y Mallén, conde de San Juan de Jaruco y de Santa Cruz de Mopox (9 volumes). The New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, the University of Miami Library, and the Florida International University Library have most of the nine volumes in their collections. (I believe only the NYPL and FIU have all 9 volumes). The Madans are in volume 5, pages 164-166, going back to Waterford, Ireland.

`Very interesting blogpost. Thank you for it. A few points (if I may — I have no desire to be irritating):

1. Since at least the 1540s, Cristóbal’s ancestors (in Waterford, Ireland; in the Canaries; and in Cuba) all spellt their (Gaelic) surname as “Madan” (Gaelic spelling), rather than “Madden” (English spelling).

2. In Spanish, the surname has no diacritical mark (i.e., no “accent” mark) — although many (non-family-members) erroneously insert one. Words ending in “n” in Spanish naturally are accented on the penultimate syllable, thus no accent mark is proper where (as here) the spoken stress occurs on that syllable. I am aware of no Spanish-language writing by any family member, from the 1670s to the present, where any accent mark is used with the surname.

3. Since you asked….: Cristóbal died in Havana on 13 April 1889, at 2:00 a.m., of “nefritis parenquimatosa”; his funeral was held the next day at Nuestra Señora de Montserrate Catholic Church, Havana; and he was buried from there at the Cementerio de Cristóbal Colón, Havana. His full Christian name (by the way) was Cristóbal Fermín Buenaventura del Carmen.

4. The authorship of the term “manifest destiny” is still a matter in dispute. The term first was used in an unsigned editorial in the July–August 1845 issue of the “Democratic Review,” whose co-editors were John Louis O’Sullivan, a Spanish-born American of Irish parentage, and his soon-to-be brother-in-law, Cristóbal Madan, a Cuban-born soon-to-be-American citizen whose paterno-paternal great-grandfather was Irish. It is unknown who of the two wrote that particular editorial. Most attribute the authorship to O’Sullivan, but the possibility of Cristóbal’s authorship has distinguished supporters, including Lord Thomas (i.e., Hugh Thomas), the celebrated historian.

5. Cristóbal’s parents had 12 children (not 6), of whom Cristóbal was the 4th (and 1st (not only) son, of 4). All but 2 of the 8 daughters lived to adulthood, as did at least 3 of the 4 sons. His parents were, indeed, first cousins, and marriages between cousins were (as you indicate) not infrequent at the time; the dispensation necessary for Cristóbal’s parents to marry was granted by Pope Pius VII on 7 March 1802.

6. Luis Gonzaga Estanislao Pedro Pedroso y Madan (husband of María Sturdza y Sturdza-Barladeanu; married 18 Sept. 1907, in Dieppe, France) was, indeed, the grandson of Cristóbal, by his second wife, Mary Jane O’Sullivan y Rowly, through their daughter, Inés María Dolores.

7. I have photographs of Cristóbal’s father, of 2 of Cristóbal’s sisters, of Cristóbal’s younger daughter, and of 1 of Cristóbal’s nephews and 2 of Cristóbal’s nieces, and I have a silhouette of Cristóbal’s mother’s brother, but (regrettably) no image of Cristóbal. I am actively seeking any images of any members of this family.

8. Considerable portions of the material in the “Historia de Familias Cubanas” relating to the Madan family are incorrect.

I almost forgot: I also have a fine caricature (drawing) of 1 of Cristóbal’s sons, by Juan Jorge Peoli y Mancebo (another “Cuban New Yorker” — of whom I have a photograph and a self-caricature), who was married to Cristóbal’s niece. The Peoli y Madan descendants have many photographs of late 19th-Century gatherings of friends (including José Martí) and family at their summer home in upstate New York.

Also, I mistakenly said in my earlier comment “Cristóbal’s younger daughter” when I ought to have put “youngest.”

Finally, I note that Cristóbal’s youngest son Julián O’Sullivan Madan y O’Sullivan continued the New York connection in the decades before his sudden death in Santiago, Chile, on 28 Deecember 1893: He married Emmie Appleton y Osgood in New York City on 7 April 1875, and their son Julian Appleton Madan y Appleton was born tin that City on 2 October 1876. The younger Julian graduated from Columbia circa 1898 and married Grace F. Ritschy y MacDermott (a New Yorker) sometime before 1916, and their daughter, Edith Appleton Madan y Ritschy was born in New York on 31 August 1916. After 1923/24, I lose sight of the younger Julian and his wife and daughter; his widowed mother Emmie married the architect Walden Pell Anderson y Phelps at St. Thomas Church on 14 November 1899, but I lose sight of her after that.

`Sorry if the trivia is too tiresome.

Uuf. What comes of typing too fast (and off the top of one’s head)…. It should be “Peoli y Alfonso” descendants, of course, not “Peoli y Madan” descendants. Cristóbal’s niece Antonia Alfonso y Madan was the wife of Juan Jorge Peoli y Mancebo, and it is their descendants to whom I intended to refer.

I promise to stop.

Dear Mr. Madan:

Thank you very much for this string of comments, which have certainly illuminated many aspects of the Madan story. I argue in my forthcoming book that Cristóbal is the most emblematic and enduring figure of the New York Cuban community, his influence and importance unappreciated. This is partly his own doing. It is clear that he chose to remain in the background in his activism, especially when it came to writing political essays, as you point out, and as is also evident in the anonymous contributions to La Verdad. Madan spans all major periods of the Cuban story in New York until the 1880s, starting with his contact with both Varela and Heredia in 1823. Perhaps I can impose on you for copies of at least one of those photographs when I assemble the illustrations for the book. It would be a shame not to include the Madan family among those pictures. Again, thank you.

Lisandro Pérez

Dear Mr. Pérez:  (Would you rather we correspond in Spanish? Nacà aquà ya en el exilio — las 5 hermanas mayores nacieron en Cuba, y nosotros 4 varones y una hembra más nacimos aquà — pero nuestros padres nos obligaron a hablar siempre entre nosotros “en Católico” — como Vd. prefiera.)  Thank you for your kind comments. I feared that I was growing tiresome with my picayune details.  I would be happy to help you in any way I can. In fact, your blogpost gave me a few ideas, and I am now on the hunt for a picture of Cristóbal, which I would be happy to provide you with if I unearth it. Otherwise, you are welcome to whatever materials, photos, or information at my disposition that you may be interested in. I assure you that it would be no imposition. We just need to discover what would, in fact, interest you.  I am descended from Cristóbal’s older sister, Isabel MarÃa de la O, who, at what is now Cathedral of Matanzas, on 14 June 1828, married her maternal uncle, Domingo Celestino Madan y Lenard, by Dispensation of Pope Leo XII granted 14 Jan 1828. One of their 9 children, Roberto MarÃa Concepción, my ancestor, a physician, lived in New York in the 1890s while receiving treatment for cancer; he returned to Cuba to die. His son (my ancestor), José “Rafael” Francisco de la Candelaria Madan y RodrÃguez-de-Armas, also lived in New York City in the 1890s, practicing as a dentist (and supporting his father), and was a member of the pro-independence “Club Oscal Primelles” there; he, too, returned to Cuba, where he married (Adela Margarita MarÃa Josefa Antonia Diago y de Cárdenas) and had a family. (On the chance that it may interest you, I attach a photo of members of this Club. Rafael is third from the left (as one faces the photo), in the back row.)  After that, my own family has no particular association with New York until my maternal grandmother, Jeannette Arechavaleta y Arroyo, went to live there post-Castro, until her death in 1987.  I look forward to hearing from you,  Rafael Madan y Casas

In my message of a short while ago (did you get it?), I inadvertently typed “Club Oscal Primelles” rather than “Club Oscar Primelles.” I apologize for my too-fast typing.